A few people have asked me why I haven’t uploaded a recommended books list of some sort, and after some consideration I’ve come to the conclusion that I don’t really know. Generally speaking, I believe that your appreciation for a written work is personal. If you read something and like it, that’s great—that’s what reading is for, after all—but you should never be surprised that it doesn’t have the same effect on others. Books, TV, food, anything that humans can consume, we metabolize them in different ways, tear apart the knowledge gained and absorb into packets of unique significance. I’ve suggested books I’ve loved to friends that I was sure would love them too, only to be met with indifference or confusion or, most commonly, a compromise. They liked the book! But they didn’t love it. And that’s fine. Different strokes for different folks.1

There’s a perfectionist aspect of me that says that I shouldn’t recommend something unless I know that they’ll appreciate it, which has made me reluctant to share my own thoughts, but I’ve realized that this shouldn’t be the case. Others might not value a certain story as much as you, but the value of a work is determined by more than the text it contains. Even two people that completely disagree on the interpretation of a work can have a conversation and come away having learned something. “Don’t waste the reader’s time,” goes Vonnegut’s first rule of writing, and at the end of the day I believe that most works of writing follow that rule. There’s always something new to learn and thoughts to think, as long as you’re willing to receive.

So for those willing, here are three literary works that have deeply influenced my writing and perspective on life, from all different genres of written fiction. You don’t have to like them—but I think they all have something important to say.2

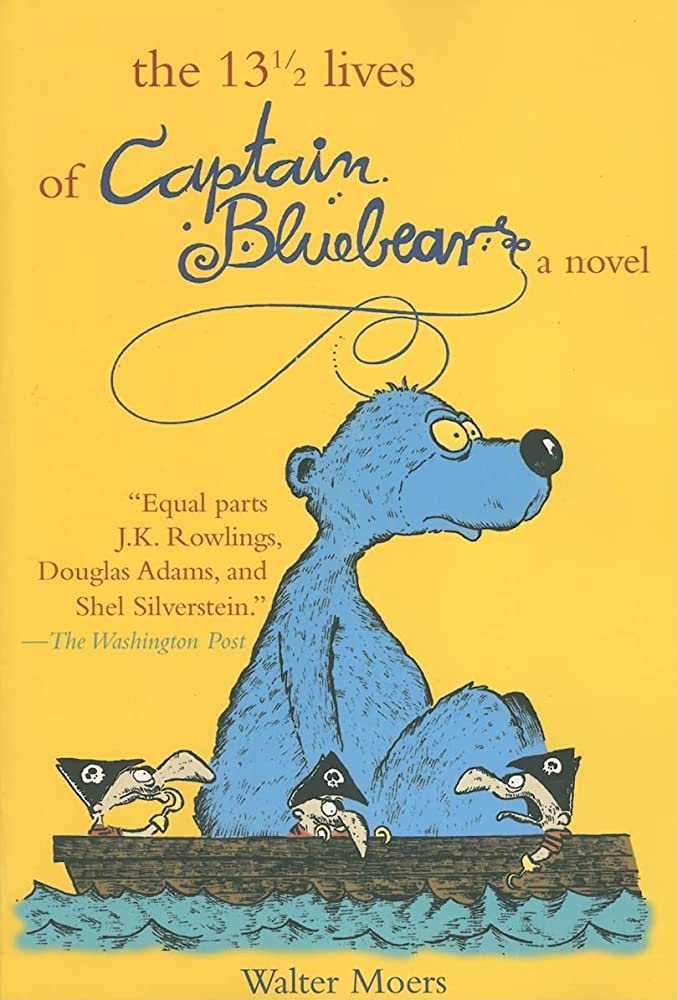

The 13½ Lives of Captain Bluebear by Walter Moers

This book is insane. If human creativity could be distilled and condensed into solid form this book would be the result, 704 pages of unpredictable, bizarre, fantastical nonsense that binds itself together into a brilliant gem. I first read it as a kid while stuck at a Buddhist temple in Detroit for four days, consigned to do nothing but eat oatmeal with raisins and anxiously fidget on prayer mats, and in spare moments the book was my only solace from boredom. It was more than enough.

Since then I’ve reread it every couple of years, and every single time I’ve fallen back in love with the beautifully-sculpted world of Zamonia and the way that the author, Walter Moers3, can paint a scene in such vivid detail that the passages of text flicker by your eyes like scenes in a movie. Moers’ writing is like Don Quixote if Cervantes was dropping acid in the back of a college mythology course for a whole semester. He has a particular knack for spinning words, sentences and phrases and soliloquies crashing into each other and dripping off the pages and oozing with inspiration from all fiction that has come before him. There are times that you start to think that you might have been tricked into reading an especially lengthy children’s book, and times when you very, very much realize that this isn’t the case.

This book made me love fiction, and it holds a certain magic that many fantasy novels seem to share; that escapism into a world at the edge of your dreams, on the horizon of reality, that peek into a young, naive, and unbridled joy which we struggle to keep a hold of as we get older. There’s several other works by Moers which take place in the same fictional setting, each of varying quality, but The 13½ Lives is by far the best, the boldest, the most stunning.

The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

Lahiri’s collection Interpreter of Maladies is widespread throughout high school English curriculums, but The Namesake is its weightier, more thoughtful cousin. The quiet contemplation and loneliness from stories like “A Temporary Matter” is brought to its fullest potential in the form of a longer text as you follow the humble beginnings of the Ganguli family in the United States. The novel takes some time to play out, but the long descriptions of immigrant life and forays into memories of the past are necessary for the book to have impact. It is a character study, examining the small troubled space of Gogol Ganguli as he attempts to find himself, moment by moment.

This work holds personal value because I think I share a lot of those same insecurities as the protagonist. The constant push-pull of cultural divides has been persistent in my life as an Korean-American4, and The Namesake shows well the alienation that can foment as one teeters on the fence, uncertain which side to embrace. The immediate answer, of course, is to embrace both—but is that any easier? There is no perfect solution to the choice I need to make; the novel, as incisive as it is, doesn’t pretend to give one, either. And yet with a yearning determination it provides a reflection for our wandering selves as we try our best to negotiate with our doubts.

As a final note, I think that The Namesake has one of my favorite endings of all time. Many stories struggle to end when they need to; they drag on and on, if only to give some kind of closure, some sense of overt finality. The Namesake ends on a simple, bittersweet note, saying what needs to be said and nothing more. It trusts the reader to fill in what happens next.

Deacon King Kong by James McBride

This book is emotional. It is funny—absurdly funny—with characters so zany they pop out from the page like fireworks, with situations so bizarre you double take as they strut by. Sportcoat, the drunk-out-of-his-basket, 71-year-old deacon, has so many odd ends and eccentricities that he feels like four characters at once, a cacophony of a human being assembled into a elderly black man who can only think straight when he’s on the hooch. And yet the novel never goes so far as to caricaturize him, instead treating with a certain respect, a veneration. He is just crazy enough to be real, just real enough to be both hysterically funny and shockingly tragic. It’s halfway through the novel that you realize that he’s not just stumbling blind through his remaining days—he’s searching. With a blend of pity and caution, you can’t help but start to root for him.

This book is sad, as a book tends to be when you write about confused lonely people lost in their own struggles. That much is no different from other works. But then, when you expect it the least, there is a fury that blazes out from the depths of the writing, so despairing and furious that it scalds the fingers as you hold the pages open, and you realize what Deacon King Kong is really all about. It is about the destruction of a people, slow and insidious and calculated and devastating, the weary pain of it all soaked into the hollow bones of a city that will never stop hungering for more, and the blind eye that the more fortunate turn to it all. It is a story that has happened again and again through the jagged, dark history of America, not with these characters or in this neighborhood but in every other way, and that pain lingers even now almost 55 years later. The book hits hard.

Don’t let the happy ending fool you; Deacon King Kong isn’t something you read to feel all nice and warm inside. McBride is a fantastic writer and yanks every loose end in your heartstrings, persuading you to stop and think for a minute about just how unfair the world can be at times.

Notes

[1] This is also why I HATE it when people judge books based on Goodreads scores. Okay, maybe an average two-star rating points towards issues. But if it’s any higher, read it for yourself! Don’t automatically disqualify a book because it doesn’t match some arbitrary four-star cutoff. Be your own judge of the work—you owe at least that much to any writer.

[2] I made several write-ups for books I had in mind, but ultimately decided to go with these three for now. I’ll upload the others at some point—a good content creator never releases everything at once.

[3] Moers is German, but many (all?) of his works have been translated by John Brownjohn, who also deserves much praise for being able to decipher what must be sheer German inanity into English prose.

[4] For a novel specifically on the Korean-American condition, I’d highly recommend Native Speaker by Chang-Rae Lee.